Exploring the path towards a biological definition of Parkinson’s Disease and its widespread implications

Date: March 2024

Authors: Francisco Cardoso, MD; Michael S. Okun, MD; Shen-Yang Lim, MD; Njideka Okubadejo, MD; Bastiaan R. Bloem, MD; and Sirwan K.L. Darweesh, MD, PhD.

Editors: Lorraine Kalia, MD, PhD; Daniela Berg, MD, PhD; Jeffery H. Kordower, PhD.

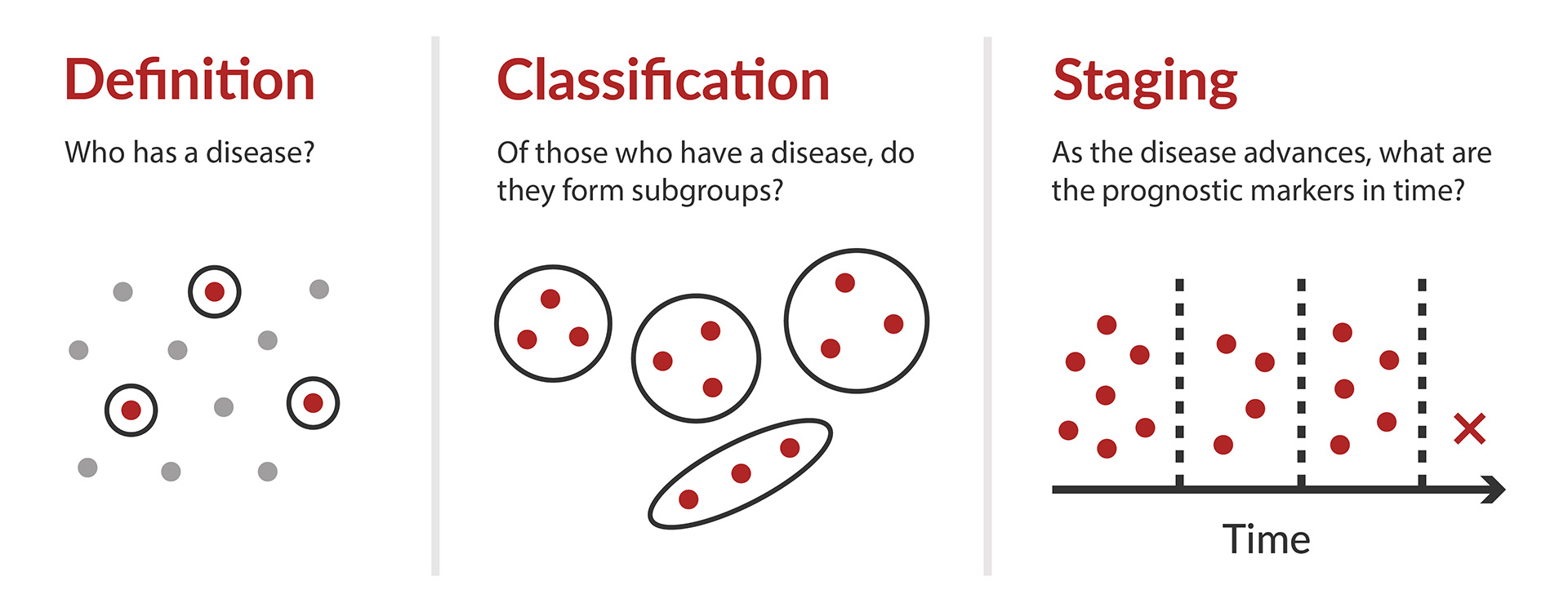

The conversation around definition, classification, and staging for Parkinson’s Disease has been sparked by a series of recent papers (Box 1). Two proposals – one by Höglinger, et al. and the other by Simuni et al. – attempt to define Parkinson’s disease based on what is currently known about the underlying pathobiological processes. Each paper then outlines a classification or staging system, respectively. Parkinson’s disease has historically been only defined by the clinical presentation of the disease, however, the unified interest in slowing progression of the disease will undoubtedly require the identification of the disease before the motor symptoms appear. Therefore, these papers represent attempts to redefine the disease in a way that could allow for earlier diagnosis. The discussion below is from a global group of leaders who examine the obstacles and implications of these proposals.

An important concept to grasp, before diving into the discussion, is the difference between these terms: Definition, Classification, and Staging.

|

MDS Consensus Statement

Proposals

Editorials

|

What is the rationale for this shift? Are there missing pieces?

Dr. Okun:

The staging of medical diseases has been around for decades, however most experts concede that the field of cancer pioneered these methods. Why would we desire ‘staging a disease?’ I love the comment in the MDS consensus statement that it ‘facilitates unequivocal allocation of individuals into groups of shared biomedical characteristics along a specific disease trajectory.' In cancer, there is the TNM classification: a primary Tumor, Nodes, and Metastasis (TNM). Pay attention: In cancer, the person’s symptoms are not part of this classical staging system. This may be different in Parkinson’s disease (PD)? Alzheimer's disease has recently developed a similar classification called ATN: Amyloid, Tau, and Neurodegeneration. Will PD be next? My guess is that, in PD, these concepts will slowly evolve over the next 3-5 years, as there are still many critical unknowns and pieces missing in the puzzle.

Prof. Cardoso:

The current attempts to define PD based on biology are inspired by what has happened in the field of cancer. In the latter, the identification of biomarkers that are associated with clinical, therapeutic, and prognostic features led to the development of definitions and stagings that are of significant help for patients and physicians. Unfortunately, this is not the case for PD, at least for the time being. In cancer there were analyses of databases with several thousand patients assessed in great detail. In contrast, in PD, the proposals reflect experts’ opinion based on a paucity of data. Moreover, it’s crucial to have a comprehensive understanding of the biological factors involved in the development of the disease, its course and therapeutic response. Unfortunately, at best, currently this knowledge in PD is fragmentary.

Prof. Lim:

I believe the primary driver for this shift is a desire to be able to detect PD at much earlier stages, in order to have a chance to intervene in the neurodegenerative process. This is because by the time patients manifest motor features and are diagnosed with “early” PD, a substantial amount of neurodegeneration has already taken place [Kordower, Brain, 2013]. As the field well knows, there have been a great number of trials of disease modification therapies (DMTs), none showing a substantial benefit [Fox, MDJ, 2018; McFarthing, JPD, 2023], and one important reason for this is the disease may already be “too far gone” for DMTs to demonstrate efficacy. The second major reason is that these trials have usually been conducted approaching PD as a single entity, whereas in reality multiple different causes and pathogenic mechanisms likely operate [Prasuhn, Molec Med, 2021]. The shift to a biological classification addresses these issues, in part: (i) PD can now be diagnosed at a much earlier stage (e.g., potentially even at birth if one harbors fully-penetrant PD gene variant(s) [Lim, JPD, 2024]); (ii) trials testing treatments targeted against α-synuclein can and should ensure that recruited participants do indeed show evidence of α-synucleinopathy, to begin with. Although finding effective DMTs is of course one of the major gaps and aims in the field, an increased emphasis on biological markers will also facilitate and spur research on multiple other fronts in PD and related disorders. Thus, I believe - at least in the research sphere - that this paradigm shift from viewing PD as a primarily clinical entity to one that incorporates new biological understanding of the disease, gleaned especially over the past decade, is timely and represents a very important step forwards for the field. It is also a natural development, particularly with the recent advent of α-synuclein seed amplifications assays (SAAs) from cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) [Siderowf, LN, 2023], and the possibility that these could be non-invasively assayed from blood [Kluge, Brain, 2022; Okuzumi, Nat Med, 2023]. However, there are important caveats, some of which have been addressed by MDS leaders during a specially convened meeting in Atlanta in April 2023 [Cardoso, MDJ, 2024], and I discuss these further below.

Prof. Bloem and Dr. Darweesh:

The diagnosis of PD currently requires the presence of a combination of cardinal motor signs, collectively known as parkinsonism. However, the pathological processes of PD begin many years before parkinsonism becomes apparent, and more than 60% of dopaminergic nigrostriatal neurons have already been lost when clinically manifest parkinsonism emerges. This advanced stage of pathology hinders the potential efficacy of disease-modifying interventions, should these become available. This conundrum forms the rationale for the neuronal α-synuclein disease (NSD) integrated staging system (NSD-ISS) and the SynNeurGe criteria. The purpose of these two frameworks overlaps; both are classification systems that define disease subtypes, including the earliest disease phases that antedate clinically manifest parkinsonism. The NSD-ISS additionally proposes a staging system that rates the putative extent or severity of the disease in an individual. The main pieces of both frameworks are the presence of genetic risk variants for PD, the presence of pathological α-synuclein, and the loss of dopaminergic neurons, although there are differences in how the classifications are operationalised. A key feature of both new frameworks is that clinical signs and symptoms are missing as disease-defining pieces, which is a deliberate choice, to allow for a diagnosis in early stages of pathology.

Prof. Okubadejo:

The heterogeneity of PD has become increasingly apparent as our understanding of the diverse underlying genetic, environmental, and molecular mechanisms that culminate in this clinically defined neurodegenerative disorder has expanded through research. Although refinements in the clinical diagnostic criteria for PD (such as the MDS clinical diagnostic criteria and the criteria for prodromal PD) have harnessed evidence-based knowledge to improve diagnostic accuracy across the spectrum of clinically evident PD, the criteria remain insufficient to identify pre-clinical disease and still rely heavily on clinical features. The quest for neuroprotective therapies with the potential to halt or slow PD pathology, and the realization that an approach driven by a presumed single mechanism of disease is erroneous have contributed to the paradigm shift to redefine, classify, and stage PD using approaches that take cognizance of the biological processes underlying PD. Furthermore, the tools for assessing response to interventions (for instance in clinical trials) are not sufficiently objective due to the lack of reliable, measurable, and sensitive biomarkers of disease progression.

What are the advantages and disadvantages of defining Parkinson's disease based on the underlying pathobiological processes?

Prof. Lim:

The main advantage as discussed earlier is that a biological classification of PD is probably imperative for the field to start seeing success in DMT trials. The main disadvantage I envisage are the potential adverse psychosocial impacts on biomarker-positive individuals lacking clinical manifestations, who will be labelled as having a disease. While clearly some of these individuals do go on to develop disease-related clinical features, the proportion who phenoconvert, and the timing at which this occurs, are currently uncertain. Importantly, cases who previously were reported to have “incidental Lewy bodies” during autopsy might now be labelled as having a “disease” even if they never experience disease symptoms during life - nor even, perhaps, subclinical evidence of neurodegeneration (e.g., “Stage 1A NSD” per the schema proposed by Simuni et al. [Simuni, LN, 2024]). While I do accept the notion that people can be considered to have a “disease” prior to the development of clinically recognizable features (at which time they could perhaps be thought of as having an “illness”), I do think that diagnosing “disease” in individuals who will never experience disease-related symptoms during their lifetime is problematic. Both groups of authors have rightly tried to mitigate these possible negative consequences by explicitly recommending that these proposals currently be adopted in the research setting only [Simuni, LN, 2024; Höglinger, LN, 2024].

Prof. Bloem and Dr. Darweesh:

A key feature of the new frameworks is that they both allow for a diagnosis based on biological traits, even in asymptomatic individuals. This new conceptualisation is a radical shift in the traditional understanding of PD and opens research opportunities, in particular for designing trials to delay or prevent parkinsonism. At the same time, we anticipate that this shift may also introduce two specific challenges. The first challenge relates to ethical and social concerns of labelling an asymptomatic individual as having a disease. This designation could be justified when informed consent is clear and the scientific foundation is strong, as in the case of fully penetrant pathogenic genetic variants in Huntington’s disease or familial Alzheimer’s disease. For the NSD-ISS and SynNeurGe frameworks, this situation might only apply to very rare fully penetrant mutations. However, both frameworks also label individuals with α-synucleinopathy and neurodegeneration as having a disease, even if they do not carry fully penetrant SNCA mutations, which introduces a considerable level of uncertainty. The second challenge relates to the risk that these research frameworks will be applied prematurely in clinical settings. Such a premature clinical implementation occurred in the Alzheimer’s field following the publication of a biological research definition of Alzheimer’s disease. This had unintended consequences, including—but not limited to—misperception among affected individuals and medical professionals of the meaning of an Alzheimer’s diagnosis as a symptomless condition with an uncertain prognosis. To avoid this scenario, we need clear guidance on the setting in which the proposed PD classifications are being applied, and on how to communicate a research diagnosis of early-stage PD pathology to research participants.

Dr. Okun:

There are many advantages and disadvantages of using the pathobiology as the sole way to define PD. The biggest risk in my mind is missing the ‘forest from the trees.’ Can we measure ‘neurodegeneration’ both anatomically and biologically? The answer is ‘sort of.’ We are pretty good at bedside examinations and awarding numbers on paper ‘scales’ as a method to rate specific symptoms. In PD, these scores on the rating scales are frequently like golf— lower numbers are better (translating to less disease). We have yet to agree on a biological definition for PD. In 2023, scientists and clinicians began more seriously considering ‘α-synuclein aggregation’ as a possible biological event; this could be a candidate for contribution to the ‘biological definition’ of Parkinson’s disease. The 2023 buzz has been all about a seed amplification assay (SAA) test. It is important to recognize that not all scientists agree that the SAA will be adequate, as the test must biologically define PD and there is a lack of consensus here. We need as a field to include stakeholders ‘front and center,’ as we are beginning to consider ‘labeling’ asymptomatic folks and those without fully penetrant Parkinson’s genes. Finally, the technology and science continues to progress quickly and there will likely be near-future tests which help to differentiate the various forms of parkinsonisms and that will surely be a welcome addition.

Prof. Okubadejo:

The current diagnostic criteria for PD anchor heavily on its classification as a movement disorder, whereas it manifests with an array of non-motor features that can predate the defining clinical characteristics. The motor features that form the basis of the ‘first level’ of diagnostic ascertainment overlap considerably with other atypical parkinsonisms, with clarity of diagnosis sometimes requiring several years of follow-up. Dopamine transporter imaging as currently applied does not distinguish PD from these neurodegenerative parkinsonisms. There is a widely acknowledged gap that earlier stages of PD that are pre-manifest (including pathological stages preceding prodromal PD) and the likely target for successful neuroprotective therapies would require biomarkers that can reliably detect biological changes. Furthermore, genetic mechanisms underlying PD vary and indicate a need for a personalized approach to developing neuroprotective and therapeutic interventions. As such, defining PD based on the pathobiology offers the advantage of more precise and objective characterization and the opportunity to develop targeted interventions and objectively monitor disease progression. On the flip side, the proposed approaches portray the complexities of utilizing a biological framework for a complex and heterogenous disease such as PD. The current biomarkers are not yet widely available or accessible, still have drawbacks in their ability to definitively diagnose PD, and there is the possibility of having a sizeable proportion of persons with PD ‘otherwise uncharacterized’ for a variety of reasons, including heterogeneity of the α-synuclein neuropathology.

Prof. Cardoso:

When there is a comprehensive understanding of all the factors involved in these processes, it is possible to understand the cause, clinical course, treatments, and prognosis of the disease. As stated in the previous answer, this is already a reality in oncology. Of note, our colleagues of the cancer field have reached this point after 80 years of intensive data collection and analysis! Unfortunately, in PD area we are just glimpsing what might underlie the disease. To move forward amid so many uncertainties and unknowns will just sow confusion and misunderstanding among professionals, PD people and their care partners.

What are the major strengths and weaknesses of each of the proposals?

Prof. Cardoso:

The two proposals reflect a patchy knowledge of the underlying processes. Their cornerstone is the presence of aggregated α-synuclein as demonstrated by the SAA (α-synuclein aggregation assay). There is growing evidence that α-synuclein is not fundamental for the development of PD. For instance, many patients with PD do not have α-synuclein either as assessed by SAA or even post-mortem studies. This is particularly true of carriers of LRRK2 mutations, a common genetic defect. Other proteins, not included in both studies, play a major role in the pathogenesis of PD. One good example is tau. A second common problem is the use of some genetic mutations in the proposals of classification and staging. They ignore that there are certainly many other mutations involved in the complex genetics of PD. There are also data showing that one given mutation can have opposite effects (protective versus toxic) depending on the ethnicity of the individual. The proposal of staging aspires to be based on biology. A mandatory requirement of a staging anchor is its correlation with the progression of the condition. Unfortunately, the anchors used by the authors, genetic mutations and SAA positivity, do not change throughout the course of PD. Just this finding completely invalidates the proposal as a staging. At the end of the day, the only variable that correlates with the progression is the MDS-UPDRS. We are back, then, to where we have been for the many past years. It must be mentioned that the staging proposal does not provide any definition of the clinical features to be used as milestones. Finally, the staging proposal simply erases the concept of PD, attempting to replace it with the so-called ‘neuronal α-synuclein degeneration’ (NSD). The issue here is not a possible disregard for history. NSD is a hodgepodge of clinical features with courses radically different. A patient with idiopathic REM sleep behavior disorder may remain decades without any other clinical feature. In contrast, an unfortunate individual with dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB) will certainly have a rapid and dramatic progression with a significantly shortened life expectancy. Yet, these so dissimilar patients are placed under the same NSD umbrella. More than a historical anathema, this is a great disservice for patients. Finally, the oncologists have always kept in mind the need to create classification and staging schema that are accessible at all the corners of the world. Putting aside the shortcomings I have discussed, the two proposals in PD are based on markers available to a small proportion of individuals. If they triumph, they will generate a huge crowd left out of them.

Prof. Bloem and Dr. Darweesh:

Both frameworks merit recognition for initiating a vital and engaging discussion on the classification and potential staging of PD across its entire course.

A strength of the SynNeurGe criteria is that they are inclusive of Parkinson’s disease without α-synucleinopathy. NSD-ISS proposes the term neuronal α-synuclein disease (NSD) to replace both PD and DLB (another acknowledged α-synucleinopathy). The latter proposal is contentious, as some individuals with the full clinical spectrum of PD signs and symptoms do not have an underlying α-synucleinopathy. NSD thus covers a substantive fraction of cases of PD and DLB, but not all. Furthermore, the NSD-ISS classifies individuals who only have α-synuclein, detected with a seed amplification assay, without evidence for neurodegeneration or clinical symptoms, as having NSD. This classification seems potentially problematic, because post-mortem studies show that some individuals with α-synucleinopathy never grew old enough to develop clinically manifest signs of parkinsonism or dementia.

However, the risk of erroneously classifying individuals who will never develop clinically manifest PD as having a disease also seems somewhat higher in the SynNeurGe criteria than in NSD-ISS framework, as the latter only endorses biomarkers with very high diagnostic or predictive accuracy for clinically manifest disease, such as CSF seed amplification assays to detect pathological α-synuclein or an abnormal DAT scan to establish dopaminergic neuronal degeneration. By contrast, the SynNeurGe criteria endorse multiple biomarkers for each component—α-synuclein positivity, neurodegeneration status, and genetic status—which leads to a broader definition of disease. For example, the SynNeurGe criteria label asymptomatic carriers of a pathogenic LRRK2 variant— which has an estimated penetrance of only 30–40%—as having PD if they exhibit a PD-related brain metabolic pattern, which is used as a proxy for neurodegeneration. This approach seems problematic, as the predictive accuracy of the metabolic pattern has not been established for carriers of a LRRK2 pathogenic variant and because the latency between the detection of the metabolic pattern to the onset of symptoms is uncertain.

A distinguishing feature of the NSD-ISS framework is that it offers a disease staging system, aiming to facilitate the assessment of biologically targeted therapeutics and to enable intervention studies at early disease stages. Once fully validated, such a classification system would indeed be valuable. However, as the authors appropriately acknowledge, there are no robust data from prospective studies to confirm whether the proposed stages are sequential and, if so, what the duration of each stage is. Therefore, the proposed staging system can only be considered as a working hypothesis at this moment, to be tested in future research.

Prof. Okubadejo:

The recent proposals published in the Lancet Neurology by Simuni et al and Höglinger et al are particularly important contributions and represent two distinct but overlapping approaches to addressing the need for incorporating a biological system into the recognition of PD (and α-synucleinopathies) specifically in the research setting. The NSD model of Simuni and colleagues proposes a biological definition and an integrated staging system anchored on disease biology (specifically the presence of neuronal α-synuclein fluid biomarker). In addition, the system incorporates dopaminergic dysfunction, clinical symptoms and signs and functional impairment attributable to NSD. As acknowledged by the authors, the proposal is exclusively for research, and is specifically focused on enabling targeted therapeutic development for NSD across the spectrum from asymptomatic disease to persons with severe functional impairment. The NSD framework is purposely restricted to individuals with α-synuclein pathology, excludes most genetic forms of PD (e.g. LRRK2 and PRKN with evidence of dopaminergic dysfunction but no neuronal α-synuclein), and does not incorporate clinical definitions of PD and DLB. Whereas the staging system implies a stepwise progression at first glance, the authors acknowledge that although this may be the case in later stages, there is insufficient data to ascertain if progression in earlier stages (e.g. asymptomatic stage 0 or 1A) will occur, and the time frame, determinants and trajectory of any progression. The ethical implications of extending this staging of asymptomatic individuals in the non-research setting, and the uncertainty of what to expect are important drawbacks alluded to by the authors. Although the proposal aims to reduce heterogeneity amongst participants engaged in future clinical trials with the biological approach, the nosology in use in the real world for symptomatic individuals and clinicians, based on currently accepted clinical diagnostic criteria for PD and DLB, is not incorporated into the scheme. Implementing these criteria broadly in research will still require further optimization of biomarkers and it is expected that future iterations will incorporate biomarkers refined with improved sensitivity and specificity.

The SynNeurGe research diagnostic criteria proposed by Höglinger et al also adopts a biological approach that acknowledges the heterogeneity of PD and adopts a 3-component classification system that defines Parkinson type synucleinopathy, PD-associated neurodegeneration, and PD-specific genetic variants. In addition, a clinical component is included in the classification system. This proposal allows for the inclusion of non-α-synuclein pathology as an underlying mechanism and envisages a broad application of the system in research scenarios beyond clinical trials of neuroprotective therapies. The proposal represents a robust consideration of PD biological and clinical complexity and heterogeneity despite the limitations alluded to by the authors. Gaps in knowledge regarding disease evolution and prognostication, and the ethical implications inherent in that for asymptomatic and early-stage individuals in the research setting are limitations that can be addressed through future research.

Prof. Lim:

I favor the proposal by Hoglinger and colleagues to retain the term PD, which is more inclusive in some respects, and obviously familiar to all (indeed, part of our Society’s name!). I agree with other commentators that replacing or subsuming PD with/under the new term NSD (which would also include several other related entities) [Simuni, LN, 2024] will cause confusion [Obeso, LN, 2024], and excludes patients displaying typical PD features whom clinicians would readily diagnose as “PD” but lacking evidence of α-synucleinopathy (e.g., the vast majority of homozygous/compound heterozygous PRKN gene variant carriers and a substantial proportion of LRRK2 gene variant carriers) (Höglinger et al. get around this by labelling this entity “Genetic synuclein-negative PD”) [Höglinger, LN, 2024]. Additionally, I have significant reservations whether there are presently sufficient scientific data to support the creation of an “NSD” entity, for example in the differentiation from clinical look-alikes, particularly multiple system atrophy (MSA), in which glial α-synuclein accumulation is primarily observed. The seminal study by Siderowf et al. involved a substantial number of subjects across multiple subgroups, but did not include MSA cases. To my knowledge, there is only one adequately-sized CSF SAA study that showed good differentiation between PD and MSA [Shahnawaz, Nature, 2020]. The reproducibility of these techniques, and their widespread applicability, to reliably ascertain neuronal α-synucleinopathy, remain question marks in my mind and I feel it may be premature to propose an in vivo diagnosis of NSD (vs., say, just “synucleinopathy”), based on the available literature.

Dr. Okun:

First, we will bear witness to multiple clinical-research groups and stakeholders ‘dialoguing and debating’ the biological classification. We should welcome this sometimes-heated discussion as ‘critically important.’ There will definitely be more discussion on the two proposed schemes: Höglinger, Adler, Lang and colleagues have proposed a research based biological classification called the SynNeurGe. It is simple: 1- presence/absence of α-synuclein or a positive seeding assay; 2- evidence of underlying neurodegeneration which is referred to as Neur (not limited to DaT scan, can be other imaging techniques), and 3- potential presence of gene variants Ge. Experts have argued that this may be more of a classification system vs a biological definition, though there is definitely overlap. Chahine, Marek, Simuni and colleagues have proposed reimagining PD (more broadly) as Neuronal Synuclein Disease (NSD). These authors would include all those folks with both a positive seeding assay and a positive DaT scan. This definition would broaden to include DLB, isolated rapid eye movement (REM) sleep behavior disorder (RBD), and asymptomatic individuals. This scheme would not include MSA. Overall, the authors propose a staging system using the CSF seeding assay, genetics, and dopamine dysfunction determined by DaT and symptoms. We can bet there will be more proposals and more hybrid changes on existing proposals in 2024. All of the stakeholders will in 2024 and beyond will be collectively challenged to develop a biological definition that predicts progression and could be plugged into a staging system. In my view, we are not there yet. The clinicians and scientists must come to terms with the failure of the seeding assay to pick up all cases, and especially the genetic forms of PD. Further, whatever system is adopted, we will be stuck with it for a long time (as evidenced by the Hoehn and Yahr); so we should take our time and get it right. The 'race is on' for a biological definition, disease staging and a classification for PD. All stakeholders should be actively involved and at the table: clinicians, basic science researchers, persons living with Parkinson’s, regulatory agencies, insurance providers, governments, and pharmaceutical/device companies.

What are the potential applications of the classification system and the staging system, and what are important caveats to consider?

Prof. Cardoso:

Correctly developed systems allow early diagnosis, understanding of the clinical features, establishment of proper and effective treatments and accurate definition of prognosis. They also improve the quality of clinical trials, increasing the odds of finding better treatments. This is what happens in oncology. I repeat, though, that unfortunately this is still a mirage in the field of PD.

Prof. Lim:

Some of the caveats have been discussed above. The enthusiasm that surely will spring from these proposals need to be tempered by these considerations, including the potential for these revolutionary changes to further widen the (already very large) gap in the care PD patients receive globally [Cardoso, MDJ, 2024; Schiess, JAMA, Neurol 2022; Lim, LN, 2019; Tan, MDCP, 2024]. That said, there are a great many potential applications of a more biology-centered approach to PD, ranging from the development of DMTs, biomarker discovery, clinical phenotyping, epidemiology, etc., which patients and the scientific community can benefit from. Studies in much earlier disease stages are very much needed, to improve upon the field’s dismal record of negative DMT studies, and using biological anchors (e.g., highly-penetrant genetic variants, α-synucleinopathy and/or dopaminergic dysfunction), before the onset of clinical features, may provide the best chance for success. There will also be beneficial spill-over from these advances into related/overlapping conditions, such as the Parkinson-plus syndromes, e.g., in one of my own areas of interest, determining to what extent concomitant α-synuclein co-pathology in progressive supranuclear palsy might explain the occurrence of clinical features like REM sleep behavior disorder or hallucinations (that have been more typically associated with α-synucleinopathy) [Lim, PRD, 2023].

Prof. Okubadejo:

As proposed by the two groups, the classification system and the staging system are useful frameworks for research which is the primary focus of the current iterations. As more evidence emerges to further validate the biomarkers and unequivocally establish their utility in distinguishing PD subtypes, refinements of the proposals and possibly a merger that allows for uniformity of the biological approach (definition, classification, and staging) across all research types would promote progress in the field. Importantly, global accessibility and capacity to implement such criteria (including incorporating provisos and evidence-based equivalences) for scenarios in which the complete set of criteria cannot be achieved will ensure that the current gaps in diversity of populations represented in clinical trials are not widened any further. Developing a harmonized schema that can be applied in practice for the diagnosis, care and monitoring of PD across all stages is also a need that should be met.

Dr. Okun:

It is not easy to harmonize thought, however we must persist in our effort(s). Persons with PD must be present for these dialogues in order to drive the necessary foundational principles and to be sure we achieve a meaningful product. We have one more important task for 2024 and beyond— educating persons with Parkinson’s, families, clinicians and the public. It is our duty to explain the differences between core definitions of disease, a biological definition, staging, classification and rating scales. It is our obligation to listen and to integrate feedback. We need to consider the following questions:

|

Are we trying to use the product to communicate with persons with disease? Are we using the product as a tool to communicate between doctors and clinicians? Are we attempting to use the product to improve clinical trials? Are we developing a tool for a diagnostic test or are we measuring disease progression? Are all the stakeholders at the table? Have we asked ourselves the question ‘what do we want?’ A biological definition, a staging system, a classification scheme or something else? Why do we want it? |

Prof. Bloem and Dr. Darweesh:

Both frameworks merit recognition for initiating a vital and engaging discussion on the classification and potential staging of PD across its entire course. Although still tentative and in need of robust validation, these frameworks have paved the way for new research into disease modification in PD, and possibly other α-synucleinopathies. They also underscore significant knowledge gaps that deserve further study. Therefore, an important caveat is that these frameworks are not ready to be applied in clinical settings yet.

What could be next steps?

Prof. Lim:

These proposals provide valuable frameworks upon which to anchor future studies, and as the authors have mentioned, the results of ongoing research will validate or refute aspects of the proposals. With further refinement, it could be expected that the field will coalesce towards a unified definition/classification/staging system that will be broadly accepted by the clinical and scientific community at large. There are many areas to be clarified and further developed. For example, α-synucleinopathy has not been fully demonstrated to be causal in the disease nor to mark its progression [Obeso, LN, 2024]. How and why a substantial number of LRRK2 G2019S carriers display neurodegeneration and clinical features, without going through an earlier "stage" (α-synucleinopathy) need to be addressed. Crucially, and as emphasized by the MDS leadership [Cardoso, MDJ, 2024], we must strive to ensure that these paradigmatic changes are accompanied by fair prospects to promote health and well-being among the global community of patients, families and biomarker-positive individuals, regardless of geography, race, or gender [Schiess, JAMA Neurol, 2022].

Dr. Okun:

The bottom line is that a ‘big reward’ is on the horizon if we can harmonize our outputs on the biological definition, classification and staging system(s) for PD. Rushing to adopt ‘the system’ in my mind is a mistake. Slowing down the bus, dialoguing, integrating new technologies and methods and encouraging everyone to consider getting ‘on board’ will be important. Further, rushing to implement changes with regulatory agencies is likely a preventable mistake which could have global consequences on access to research and possibly even care. Finally, we should consider that the ideal framework should be flexible in embracing improvements in methods and technology, which may be more affordable, accessible, and accurate.

Prof. Cardoso:

At this moment, the first and most important step is to clearly demonstrate to the whole PD community that the current proposals are a threat to patients and science. If not rebutted, they will lead us to roads that will certainly imperil the progress that we so much wish to happen. A second step is the establishment of global collaboration to raise data that can accurately and comprehensively describe the biology, pathology, pathogenesis, clinical features, and prognosis. Once the analysis of these data is available, it will be the time for the development of PD definition and staging.

Prof. Okubadejo:

Developing a harmonized system that takes into consideration the various research questions regarding PD and allows its uniform application to all types of PD research while having utility for clinical practice. Such a system would require accumulation of evidence that may not already be available and should therefore be prioritized by research funders globally to accelerate adoption of a robust system. While acknowledging that the quest for a ‘perfect’ system should not hamper the conversation, the PD field should urgently adapt a framework that is sufficiently justified by existing evidence but also amenable to revision as current information emerges.

Prof. Bloem and Dr. Darweesh:

As we move towards a validated biological definition of PD, it would benefit the field if both frameworks, once updated, are unified into a single, integrated framework. We hope and foresee that the International Parkinson and Movement Disorder Society could play an important unifying role in this regard and be of critical importance in positioning and disseminating the new classification system to the scientific and ultimately also the clinical community.

References

Cardoso F, Goetz CG, Mestre TA, Sampaio C, Adler CH, Berg D, Bloem BR, Burn DJ, Fitts MS, Gasser T, Klein C, de Tijssen MAJ, Lang AE, Lim SY, Litvan I, Meissner WG, Mollenhauer B, Okubadejo N, Okun MS, Postuma RB, Svenningsson P, Tan LCS, Tsunemi T, Wahlstrom-Helgren S, Gershanik OS, Fung VSC, Trenkwalder C. A Statement of the MDS on Biological Definition, Staging, and Classification of Parkinson's Disease. Mov Disord. 2023 Dec 13. doi: 10.1002/mds.29683. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 38093469.

Fox SH, Katzenschlager R, Lim SY, Barton B, de Bie RMA, Seppi K, Coelho M, Sampaio C; Movement Disorder Society Evidence-Based Medicine Committee. International Parkinson and movement disorder society evidence-based medicine review: Update on treatments for the motor symptoms of Parkinson's disease. Mov Disord. 2018 Aug;33(8):1248-1266. doi: 10.1002/mds.27372. Epub 2018 Mar 23. Erratum in: Mov Disord. 2018 Dec;33(12):1992. PMID: 29570866.

Höglinger GU, Adler CH, Berg D, Klein C, Outeiro TF, Poewe W, Postuma R, Stoessl AJ, Lang AE. A biological classification of Parkinson's disease: the SynNeurGe research diagnostic criteria. Lancet Neurol. 2024 Feb;23(2):191-204. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(23)00404-0. PMID: 38267191.

Kluge A, Bunk J, Schaeffer E, Drobny A, Xiang W, Knacke H, Bub S, Lückstädt W, Arnold P, Lucius R, Berg D, Zunke F. Detection of neuron-derived pathological α-synuclein in blood. Brain. 2022 Sep 14;145(9):3058-3071. doi: 10.1093/brain/awac115. Erratum in: Brain. 2023 Jan 5;146(1):e6. PMID: 35722765.

Kordower JH, Olanow CW, Dodiya HB, Chu Y, Beach TG, Adler CH, Halliday GM, Bartus RT. Disease duration and the integrity of the nigrostriatal system in Parkinson's disease. Brain. 2013 Aug;136(Pt 8):2419-31. doi: 10.1093/brain/awt192. PMID: 23884810; PMCID: PMC3722357.

Lim SY, Tan AH, Ahmad-Annuar A, Klein C, Tan LCS, Rosales RL, Bhidayasiri R, Wu YR, Shang HF, Evans AH, Pal PK, Hattori N, Tan CT, Jeon B, Tan EK, Lang AE. Parkinson's disease in the Western Pacific Region. Lancet Neurol. 2019 Sep;18(9):865-879. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(19)30195-4. Epub 2019 Jun 4. PMID: 31175000.

Lim SY, Dy Closas AMF, Tan AH, Lim JL, Tan YJ, Vijayanathan Y, Tay YW, Abdul Khalid RB, Ng WK, Kanesalingam R, Martinez-Martin P, Ahmad Annuar A, Lit LC, Foo JN, Lim WK, Ng ASL, Tan EK. New insights from a multi-ethnic Asian progressive supranuclear palsy cohort. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2023 Mar;108:105296. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2023.105296. Epub 2023 Jan 20. PMID: 36682278.

Lim SY, Klein C. Parkinson’s disease is predominantly a genetic disease. J Parkinson Dis. In press.

McFarthing K, Buff S, Rafaloff G, Fiske B, Mursaleen L, Fuest R, Wyse RK, Stott SRW. Parkinson's Disease Drug Therapies in the Clinical Trial Pipeline: 2023 Update. J Parkinsons Dis. 2023;13(4):427-439. doi: 10.3233/JPD-239901. PMID: 37302040; PMCID: PMC10357160.

Obeso JA, Calabressi P. Parkinson's disease is a recognisable and useful diagnostic entity. Lancet Neurol. 2024 Feb;23(2):133-134. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(23)00512-4. PMID: 38267175.

Okuzumi A, Hatano T, Matsumoto G, Nojiri S, Ueno SI, Imamichi-Tatano Y, Kimura H, Kakuta S, Kondo A, Fukuhara T, Li Y, Funayama M, Saiki S, Taniguchi D, Tsunemi T, McIntyre D, Gérardy JJ, Mittelbronn M, Kruger R, Uchiyama Y, Nukina N, Hattori N. Propagative α-synuclein seeds as serum biomarkers for synucleinopathies. Nat Med. 2023 Jun;29(6):1448-1455. doi: 10.1038/s41591-023-02358-9. Epub 2023 May 29. PMID: 37248302; PMCID: PMC10287557.

Prasuhn J, Brüggemann N. Genotype-driven therapeutic developments in Parkinson's disease. Mol Med. 2021 Apr 19;27(1):42. doi: 10.1186/s10020-021-00281-8. PMID: 33874883; PMCID: PMC8056568.

Schiess N, Cataldi R, Okun MS, Fothergill-Misbah N, Dorsey ER, Bloem BR, Barretto M, Bhidayasiri R, Brown R, Chishimba L, Chowdhary N, Coslov M, Cubo E, Di Rocco A, Dolhun R, Dowrick C, Fung VSC, Gershanik OS, Gifford L, Gordon J, Khalil H, Kühn AA, Lew S, Lim SY, Marano MM, Micallef J, Mokaya J, Moukheiber E, Nwabuobi L, Okubadejo N, Pal PK, Shah H, Shalash A, Sherer T, Siddiqui B, Thompson T, Ullrich A, Walker R, Dua T. Six Action Steps to Address Global Disparities in Parkinson Disease: A World Health Organization Priority. JAMA Neurol. 2022 Sep 1;79(9):929-936. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2022.1783. PMID: 35816299.

Shahnawaz M, Mukherjee A, Pritzkow S, Mendez N, Rabadia P, Liu X, Hu B, Schmeichel A, Singer W, Wu G, Tsai AL, Shirani H, Nilsson KPR, Low PA, Soto C. Discriminating α-synuclein strains in Parkinson's disease and multiple system atrophy. Nature. 2020 Feb;578(7794):273-277. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-1984-7. Epub 2020 Feb 5. PMID: 32025029; PMCID: PMC7066875.

Siderowf A, Concha-Marambio L, Lafontant DE, Farris CM, Ma Y, Urenia PA, Nguyen H, Alcalay RN, Chahine LM, Foroud T, Galasko D, Kieburtz K, Merchant K, Mollenhauer B, Poston KL, Seibyl J, Simuni T, Tanner CM, Weintraub D, Videnovic A, Choi SH, Kurth R, Caspell-Garcia C, Coffey CS, Frasier M, Oliveira LMA, Hutten SJ, Sherer T, Marek K, Soto C; Parkinson's Progression Markers Initiative. Assessment of heterogeneity among participants in the Parkinson's Progression Markers Initiative cohort using α-synuclein seed amplification: a cross-sectional study. Lancet Neurol. 2023 May;22(5):407-417. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(23)00109-6. PMID: 37059509; PMCID: PMC10627170.

Simuni T, Chahine LM, Poston K, Brumm M, Buracchio T, Campbell M, Chowdhury S, Coffey C, Concha-Marambio L, Dam T, DiBiaso P, Foroud T, Frasier M, Gochanour C, Jennings D, Kieburtz K, Kopil CM, Merchant K, Mollenhauer B, Montine T, Nudelman K, Pagano G, Seibyl J, Sherer T, Singleton A, Stephenson D, Stern M, Soto C, Tanner CM, Tolosa E, Weintraub D, Xiao Y, Siderowf A, Dunn B, Marek K. A biological definition of neuronal α-synuclein disease: towards an integrated staging system for research. Lancet Neurol. 2024 Feb;23(2):178-190. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(23)00405-2. PMID: 38267190.

Tan AH, Cornejo-Olivas M, Okubadejo N, Pal PK, Saranza G, Saffie-Awad P, Ahmad-Annuar A, Schumacher-Schuh AF, Okeng'o K, Mata IF, Gatto EM, Lim SY. Genetic Testing for Parkinson's Disease and Movement Disorders in Less Privileged Areas: Barriers and Opportunities. Mov Disord Clin Pract. 2024 Jan;11(1):14-20. doi: 10.1002/mdc3.13903. Epub 2023 Nov 29. PMID: 38291851.