Hot topics and controversies on Stiff Person Spectrum Disorders (SPSD)

Date: September 2023

Prepared by SIC Member: Mario Cornejo-Olivas, MD

Authors: Bettina Balint, MD; Kailash Bhatia, MD, PhD

Editor: Lorraine Kalia, MD, PhD

Introduction

Stiff person spectrum disorders (SPSD), including Stiff Person Syndrome (SPS), are rare autoimmune related disorders with broad phenotype spectrum caused by antibodies against neuronal proteins. Currently, there are significant challenges with diagnosing and managing SPSD. Here Prof. Bettina Balint and Prof. Kailash Bhatia discuss some of the challenges as well as controversies regarding diagnosis, associated comorbidities, and treatment of SPSD.

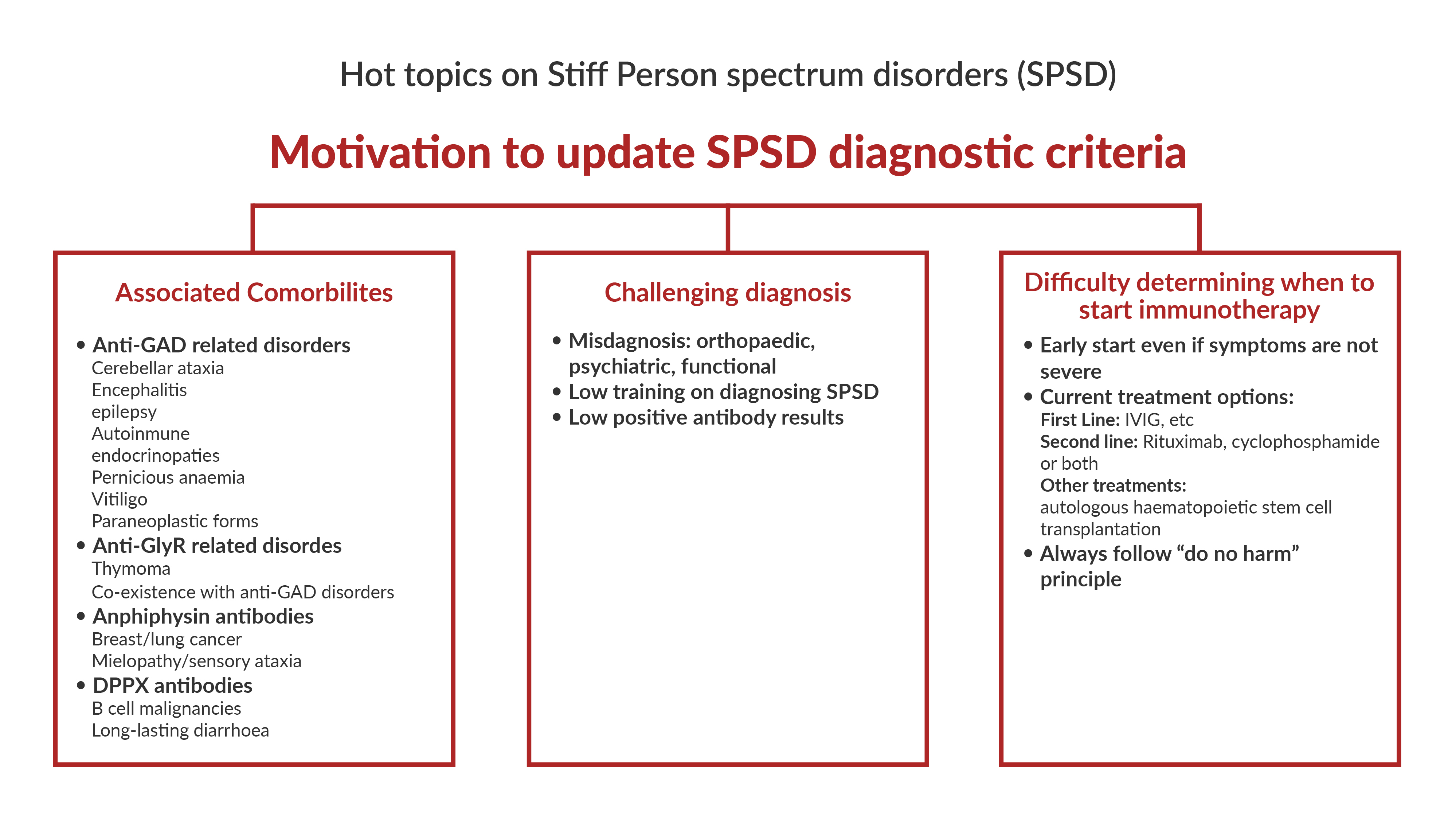

1. What factors contribute to the delay in diagnosis of stiff person spectrum disorders (SPSD)? Are updates to the diagnostic criteria needed?

Prof Bettina Balint

Patients with SPSD often face a long odyssey, typically several years, prior to receiving the correct diagnosis and treatment. The most frequent misdiagnosis are orthopaedic (degenerative spine disease, and unnecessary or even harmful surgery is not infrequent), psychiatric, psychosomatic, or functional neurological disorder. The most important factor here is probably that many physicians are not familiar with the clinical presentations of SPSD, hence we need to strive for better education and more awareness.

On the other hand, an erroneous diagnosis of SPSD is an increasing problem. Here, the misdiagnosis is often based on low positive antibody test results. This also potentially endangers patients in the era of new and escalated immunotherapies, including the wider use of autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation.

We hope both aspects can be addressed by updated diagnostic criteria.

2. What recent advances have been made around biomarker development for diagnosis and prognosis of SPSD?

Prof Bettina Balint and Prof Kailash Bhatia

Overall, the main advances lie within the identification of various antibodies and a better understanding of their role as biomarker of different immunopathophysiologies.

3. What comorbidities can be associated with SPSD?

Prof Bettina Balint and Prof Kailash Bhatia

If we divide SPSD by underlying immunopathophysiology, the biggest group is those with antibodies against glutamic acid decarboxylase (GAD). Anti-GAD autoimmunity involves other neurological syndromes like cerebellar ataxia, focal (often temporal lobe) epilepsy, and limbic encephalitis. It also associates with various autoimmune endocrinopathies like type 1 diabetes and thyroid disease, as well as with pernicious anaemia and vitiligo. In contrast, paraneoplastic forms of anti-GAD SPSD are overall rare.

SPSD with glycine receptors (GlyR) antibodies should be evaluated for thymoma. GlyR antibodies can co-occur with GAD antibodies, so what was mentioned above applies here as well. Amphiphysin antibodies are a strong indicator of an underlying breast or lung cancer. SPSD variants with DPPX antibodies may have B cell malignancies in a small proportion of cases.

Regarding the expanded phenotypic spectrum of SPSD – i.e., beyond stiffness, spasms and hyperekplexia – there are of course phenotypes with prominent myoclonus (what Prof David Marsden termed “jerking stiff man”) and other brainstem signs (e.g., oculomotor disturbance including gaze palsies and ptosis) as in the variant of progressive encephalomyelitis with rigidity and myoclonus (PERM). There are also variants with other features pertinent to the respective antibody as outlined above: with GAD antibodies, frequently cerebellar ataxia and less frequently epilepsy; with amphiphysin antibodies, myelopathy (e.g., with sensory ataxia); with DPPX antibodies, long-lasting diarrhoea.

4. When is the best time to start immunotherapy in SPSD: early versus waiting for disease burden? What is your approach to refractory cases?

Prof Bettina Balint and Prof Kailash Bhatia

These are important questions and, ultimately, the answers require studies and data that we do not have. Given that in most autoimmune CNS diseases, the paradigm has shifted to treating early, we would argue for an early start of immunotherapy also in SPSD, with the aim to stop the immune process even if the current symptoms are not severe. Some cases respond well to first line treatment (e.g., IVIG) and some do not. Second line therapy includes Rituximab or Cyclophosphamide, or a combination of both. Some centres have reported beneficial responses to autologous haematopoietic stem cell transplantation in SPSD. Of note, there are cases that seem to not respond to immunotherapy (anymore?), and the “do no harm” principle needs to be kept in mind.